Features

While artifacts are portable objects modified and used by humans, the term feature describes the non-portable components of an archaeological site. Archaeological features can include many different types of buildings, structures and changes to the landscape such as temples, houses, middens, burials, caches, hearths, floors and even postholes. Archaeologists often identify features as clusters of artifacts, patterns that represent past activities, or events like cooking and storing food. The artifacts and ecofacts associated with a feature, along with any identifiable patterns in feature organization or lay-out, provide evidence that archaeologists use to help reconstruct past human behaviors and group organization. Diagnostic artifacts and organic materials like charcoal and bone that are found within or in association with a feature can sometimes be used to date archaeological features.

Burned rock hearths, or cooking features, are one of the most prevalent feature types found at archaeological sites in Texas. Stone cooking technology is a key characteristic of the Archaic time period (~ 8800 – 1200 years before present) as a shift from hunting Pleistocene megafauna to hunting smaller mammals and the increased use of plant food resources occurred. The use of heated rocks (sometimes called “hot rocks”) to bake plant foods is evidenced by layered basin-shaped hearth features called earth ovens. This evidence shows that Archaic subsistence patterns were heavily reliant on a carbohydrate source (plant foods) that required special labor intensive preparation involving heating stones for their thermal retention properties and placing them within earth ovens to bake plant foods. Other burned rock features include flat hearths, discard or refuse piles, and burned rock middens.

Burned rock features are occasionally found in primary context, meaning archaeologists were able to identify patterns that represent the remains of intact cooking facilities. Alternatively, secondary features are characterized as scatters of fire-cracked cooking rocks from disassembled or disturbed cooking features. Sometimes referred to as concentrations, secondary burned rock features include clusters or groups of burned rock that do not fit within any of the defined feature types, but are still isolated and distinguishable from a midden.

Burned rock middens, another common feature type found in archaeological sites in Texas, represent the accumulation of discarded rock material that was used in earth oven cooking, open air cooking and hearths during prehistoric times. Some sites in Central Texas, like the Spring Lake site, have large midden accumulations that are completely buried (subsurface features) and can span many meters across a site. Therefore, while excavating a 1 x 1 meter unit, a burned rock midden may look more like a zone with a high concentration of burned rock or Fire Cracked Rock (FCR); locating isolated features is not always possible without excavating a very large area of adjoining excavation units.

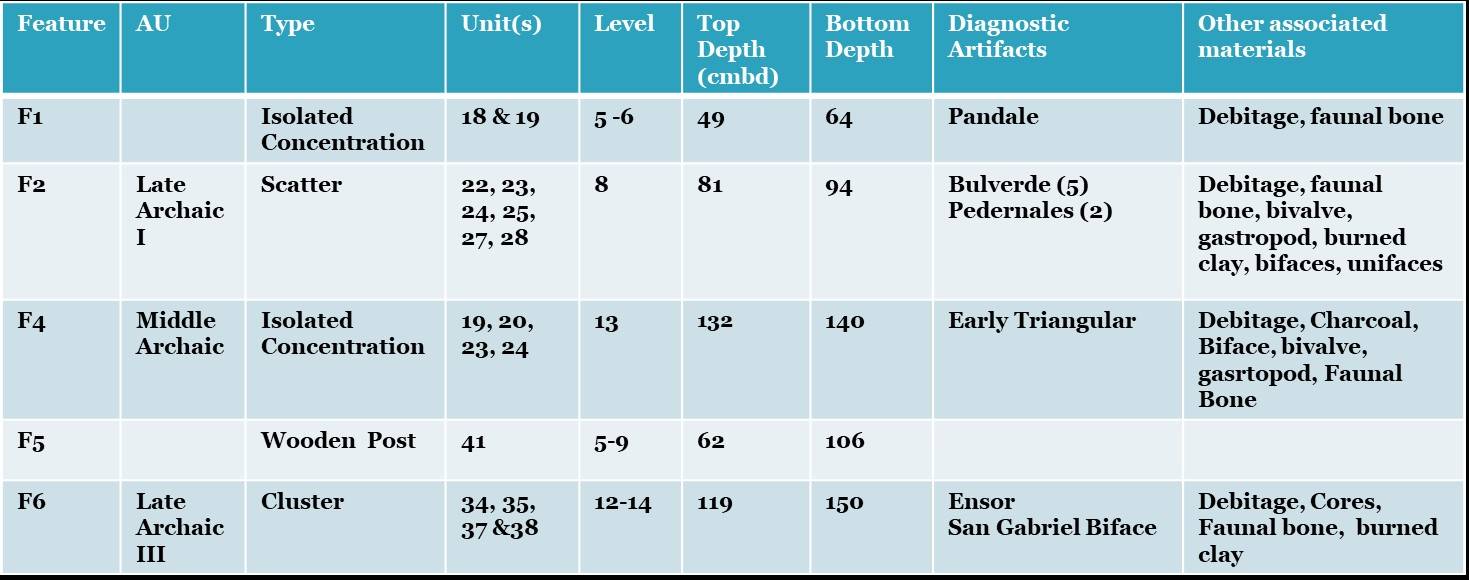

During the course of the 2014 excavations at Spring Lake, five features were identified. All of the observed features consisted of burned rock concentrations that represent various ovens or hearths. These features will be subject to further analysis and once our studies are complete, the results (including photos, drawings and complete descriptions) will be made available here in this section of the Spring Lake Data Recovery website.

How does chert get burnt?

Very often, the lithic materials recovered from an archaeological site will show some signs of having been heated, such as potlidding or crazing. Potlidding is caused when a small pocket of moisture within the chert expands faster than the surrounding stone during heating, causing a small round or oblong divot - the pot lid - to pop off of the main piece of chert. Crazing is a network of cracks in the surface of a stone caused by over-heating. Sometimes, the stone will even fracture along sharp planes, creating an angular shape that archaeologists can recognize as having been caused by fire. The color of the stone may also change, due to the oxidation of iron or other minerals.

Most of the time, burning of lithic artifacts was probably accidental. Discarded tools - even projectile points - often ended up in the fill dirt that was used to cover up an earth oven. While the oven was hot, the tools were heated as well. Other times, poorly formed chert was deliberately heated and baked in order to vitrify the crystals and make the chert more amenable to being flaked for tools, or to make finished tools harder. Tools that have been intentionally heat-treated sometimes have a slick or waxy feeling surface due to the melting and re-solidifying of the crystal matrix.

Feature 6 stands out among the others due to the significant amount of burned clay that was found associated with the feature. Feature 6 consists of a high concentration of burned clay above and within a dense cluster of burned rock. At this time, it is not known if the burned clay is simply the result of the clay rich soils surrounding the feature becoming burned indirectly during oven use, or if it is an indication that the feature itself is functionally different than an earth oven. Interestingly, a large round ball of burned clay was recorded in the Northeast corner of the feature. This specimen exhibits a circular darkened center (reduced) completely contained within a reddened (oxidized) exterior, suggesting it was exposed to high heat on all sides. Although most of the specimen remains buried in the North wall of excavation unit 34, a portion of this burned clay sphere was sampled along with additional samples of burned clay and matrix from within the feature. More oxidized burned clay was found along the east wall of the profile.

In addition to burned clay and burned rock, archaeologists recovered lithic debitage, bifaces, cores, flake tools and faunal bone in association with feature 6. Faunal and archaeobotanical analyses are also planned for this feature, which will help us piece together clues to better understand the function of this feature.

A complete dart point was also found from within the feature with a potlid still in place (see sidebar). This point has been typed as an Ensor, suggesting the feature may have been used during the Late Archaic III time period (2150-1270 years before present). However, multiple lines of evidence should be considered when assigning a date to Feature 6 including both AMS radiocarbon dating and thermoluminescence dating.

Two charcoal samples from Feature 6 produced a date range of 5470 - 5310 CAL yr. BP, a much older date than the Ensor point suggests.

A burned clay sample from Feature 6 was also submitted for a dating technique called thermoluminescence. The sample was assigned a date range of 4200 - 3900 years ago, which is older than the Ensor point but younger than the charcoal samples.

The final date of the feature is unknown at this time. Is it possible that the feature was reused over thousands of years? Take a look at the images below. How would you interpret Feature 6?